Anne Manley and Francisco Coloane

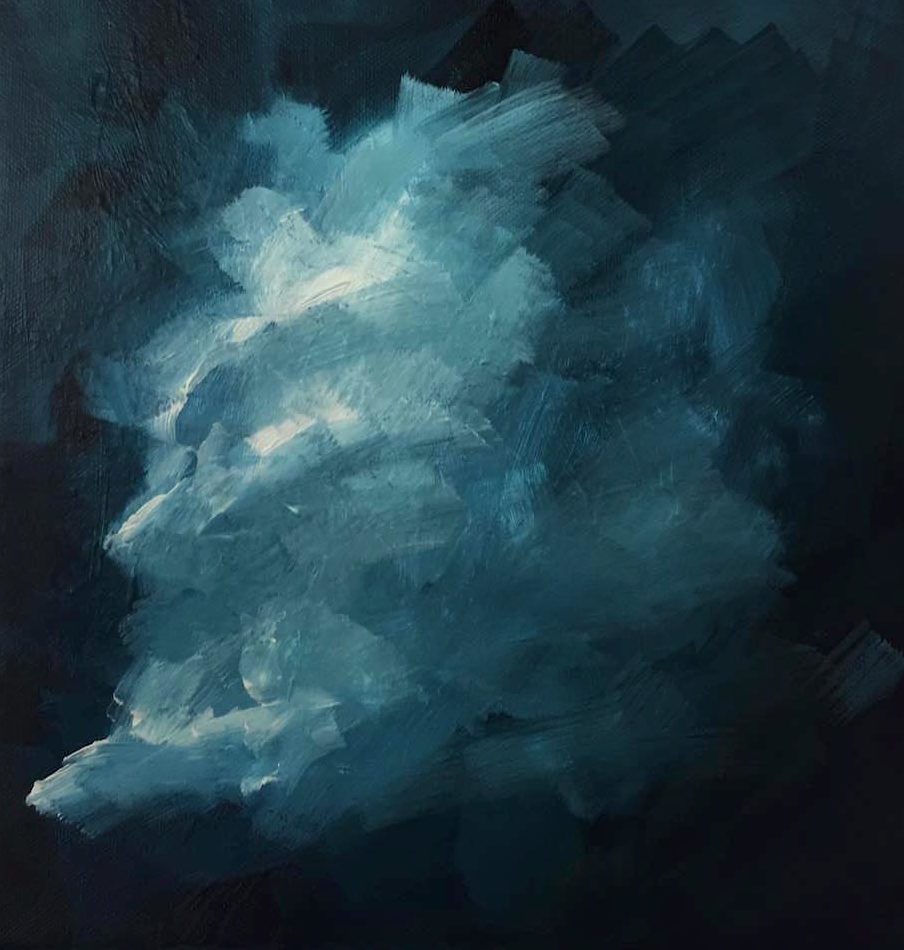

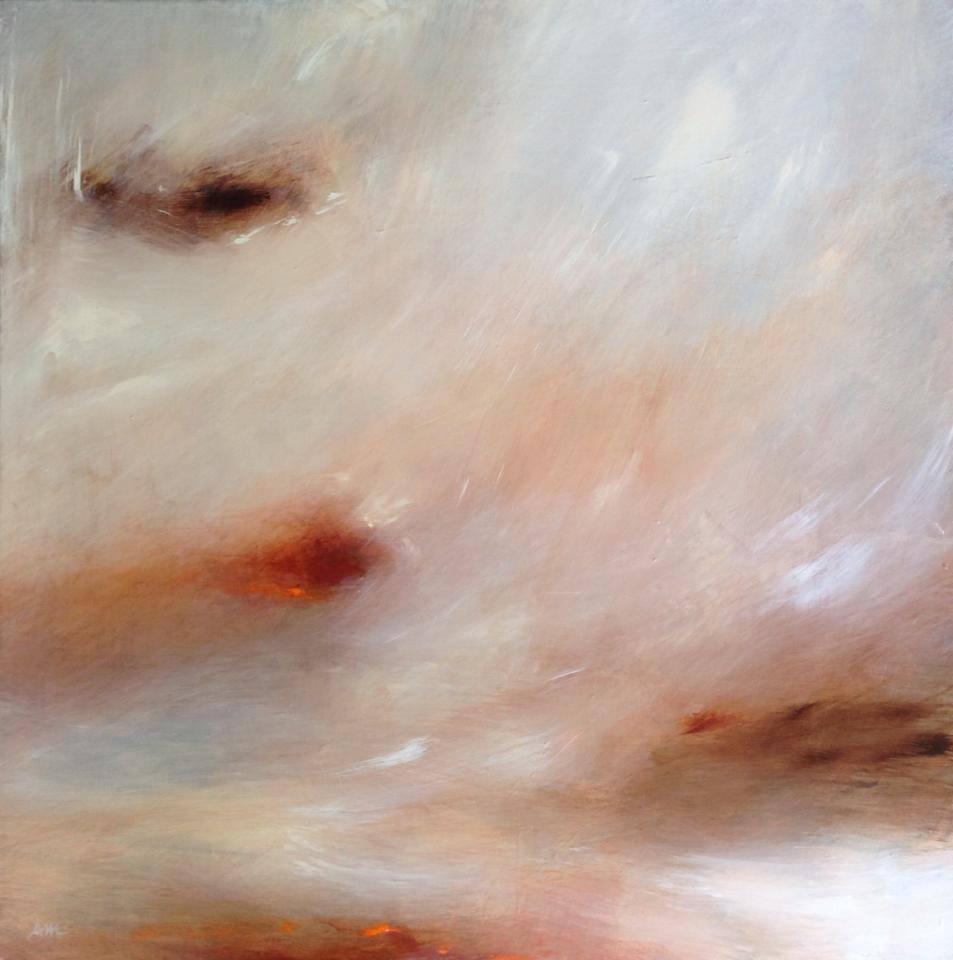

One of my favorite games is finding connections between subject apparently extraneous. More the subjects are different for essence and matter, more I have fun. Though in this case the connections between Anne Manley’s paintings and Francisco Coloane’s stories revealed themselves almost immediately. Both the american painter and the Chilean writer know how to evoke atmospheres, shadows, lights. Their descriptive sensitivity, abstract in Manley and narrative in Coloane, is so intense that it let us touch the depth of the abyss.

If paintings narrate stories, books describe images. Maybe this is the reason why I’ve always loved reading. I see Literature and Art as similar openings on an invisible world, made by perceptions, possibilities, experiences.

One particular Coloane’s story recalls the ice atmospheres of Manley’s paintings: The Hidden part of the iceberg, part of the book La Tierra del Fuego (1956). So here you go an extract of Coloane’s novel illustrated by Anne Manley. Have a nice reading.

The Hidden part of the iceberg

A man in gray dust coat emerged from the sentry box on the quay, walked up to me, and said: “Do you want to go work on Navarino?”. “Navarino?” I replied, trying to remember.

“That’s right, Navarino!” he said. “The big island to the south of the Beagle Channel. They need someone there who can turn his hand on anything”. This offer caught me on one of those days when you can set sail in any direction, and a moment in which I was wandering the harbor as if separated from myself, like those scraps of cloud that linger in the sky after a storm and that blow away as soon as the first wind arrives. Something like a storm had indeed occurred inside me, but all that remained of it was the memory of a woman ran through my veins.

When I signed the contract, however, I didn’t feel the same joy I’d felt on other occasions when I had made some life-changing decision. I was free and I was unemployed, and perhaps I was losing something by abandoning that limbo of idleness and agreeing, for some obscure reason, only half-conscious of what I was doing, to accept that offer to got o Navarino.

The quay in Punta Arenas, carpeted with snow, jutted out like a dark shadow into the sea and the night. Beside it, the coastal cutter Micalvi was belching smoke, ready to depart, waiting only a group of gold prospectors who were on their way to Lennox and Picton Islands to finish boarding. The creaking of winches mixed with the voices of men, a few drunk – they were wiser than me, using alcohol to give them the push they needed to go from one life to another. Three men were supervising the loading of machinery and provisions, and their brand new leather clothes and the awkwardness with which they gave their orders marked them out as city men unaccustomed to this kind of work. Their voices sounded shrill, nervous and impatient, and among the thirty or so workers, several muttered oaths under their breaths at the vacillation and indecisiveness of these masters.

The sailors looked on with a certain indifference as the gold prospectors came noisily on board. Some smiled, remembering other expeditions they had seen leave with high hopes, just like this one, but much better organized, only to return as poor as ever, their numbers decimated by hunger, mutiny and greed for gold. At nine, the cutter sounded its siren for the third time, as per regulations. The vessel cast off and gradually moved away from the quay as it turned at anchor, setting a southeasterly course. Soon, the town dissolved into crown of diamonds at the edges of the Straits.

Apart from the noisy gold prospectors, who never stopped checking their equipment, the passengers included settlers from the islands as well as loggers headed for the most remote and deserted coves. I learned my elbows on the rail in a corner of the deck and started whistling a tune that often brings back pleasant memories, sensations and colors, like those Bengal lights that used to be lit on Christmas nights when I was child.

The cutter advanced like a heavy gray monster, leaving a white wound on the surface of the sea and a smoky halo in the night. The engines gasped monotonously in time with my song and, thus united, we seemed to sink into darkness. Around midnight, sleep started to brush me with its raven’s wing. I had probably only been lingering on deck in order to avoid lying awake in the grim surroundings of third class. I heeded the call and went down to steerage.

Third class is the same everywhere, whether on land or at sea, and those of us who are part of it are also the same. We constitute a kind of frontier of humanity – we are like the crust of the earth, forever on the outside, exposed to the friction of the elements, the breath of the stars, while the opaque ball inside turns eternally in the darkness of space. Third class on the Micalvi was no exception. Located in the upper part of the forward hold, it looked like a prison cell with its iron bunks one on top of the other, and perhaps it was this resemblance that reminded me o a lesson I had once been taught by a prisoner. I put the straw mat over my body as a blanket, instead of under me, and settled down to sleep. The next day, we woke up in the channels that descend until they join the northeastern arm of the Beagle Channel.

The air was as clear as I have ever seen it. The mountains between which we were sailing were like herds of sea monsters cast on the waters, their white backs polished smooth by the winds. The channel broke off for stretch and the capricious waters of the Pacific rushed through, rocking the ship from port to starboard as it passed, before bursting on the coastal cliffs in a rose garden of foam.

The gold prospectors wandered the forecastle, calmer and quiete now. Rich settlers, with their wives and daughters, socialized on the bridge with the officers. When the light was too strong for me, I slid past anonymous, shadowy figures in the corridors and went and settled in the stern, near a group of four people, among whom one man stood out, a huge man with a square head, his eyes and lips hidden a tangle of hair. I discovered later that he was one of the richest ranchers along the Beagle Channel, a Yugoslav who preferred the company of the workers to that of the officers.

The group stood there as if they were talking to each other, but no one moved and no spoke. After a long while, the huge Yugoslav raised an arm as heavy as derrick, pointed at some rocks about four hundred feet from the ship, and said in a husky voice, “I once spent seven days on that rock!”. The voice was like thunder, but his stuttering delivery and the way he prolonged the “s”, changing into a “ch”, made it sound like a child’s voice. The overall impression was nor so much comic as downright peculiar. “I almost died”, he continued. “I ate twenty raw beans a day! There are Indians there somewhere, but not a single one showed himself!”. And that was all he said. The other members of the group made no comment, looked away from the rocks, and resumed their previous hieratic poses.

In vivid contrast to this sobriety, a thin, dark-complexioned man of medium height was arguing loudly with an officer on the bridge. “Puorco, madonna!” he cried in a mixture of Italian and Spanish. “What do you interessare, passage, ticket paid! Io doing it da solo, okay, io not sopportare all this! Puorco, madonna!”. The officer remained imperturbably calm, while the other man waved his arms about as if on the verge of attacking him.

He was a well-known seal hunter of Neapolitan origin named Pascualini, famous in the region for his travels and especially for having helped Radowisky, the anarchist who had “liquidated” Colonel Falcón in Buenos Aires, to escape from the penitentiary in Ushuaia. He was protesting because they wouldn’t agree to land him where we were at the moment. But he managed to convince the officer and the cutter reduced speed. Pascualini lowered his little boat, which was no more than fifteen feet long, put a little sack of provisions on board, tied one the oars to the bench in the middle as a mainmast, hoisted a blanket tied to a broomstick as a sail, put the other oar in place, sat down next to it ans with a booming “Addio” cast off and sailed away, helped by a favorable south-westerly wind.

“The man’s a hobo of the seas!” someone on board said. “He lives among the Indians for a while and then one day he approaches the first passing boat, stops it the way he just did, and brings his harvest of otter skins and seal skins on board.” After three days, the Micalvi had let off most of its passengers in various spots. The gold prospectors got off on Lennox Island. I was the last to disembark, in Puerto Robalo, after the cutter had almost completely circled the island of Navarino.

Puerto Robalo is at the foot of a range of mountains that falls almost sheer to the sea, which makes the little valley that runs alongside the coast look like a refuge of dwarves in a land of giants. The rock formation here, at this point where the Beagle Channel is about to flow into the Atlantic, creates an unusual current, with the waters intersecting and interweaving, forming whirlpools at high tide.

Harberton was waiting for me. He was a tall, elderly man, with a face as rough and dark as the bark of an oak. He wore a coat of thick one-black cloth which time had turned up brim that made him look like a Protestant pastor. “Hello”, he said in a surly tone, and in a way that made it sound as if we had always known each other. He led me to a house built out of thick logs, with a zine roof, standing beside an oak wood. Inside, I met a young Indian woman and four children.

My work consisted of helping to watch over two thousand sheep, putting the few cows in their pens, yoking a team of oxen from time to time, setting the trammel net whenever it was necessary to supply the kitchen with fish, and few other tanks. The work was very easy, and I realized that my presence there was more or less superfluous, because Harberton did almost everything himself, and took his time about it, too. On the other hand, I soon changed my opinion about the place. There was plenty of time to spare, and the work was almost a game. I milked the cows, collected firewood in the forest, tramped the paths in search of lost livestock, and in the mornings, when I pulled in the net, it was a delight to watch the glistening sea bass leaping in the bottom of the boat, like dozens of severed arms.

At first, everything went very well in that idyllic spot. I say “at first” because it was only after two or three weeks that I really became aware of something strange, something that was gradually to drive me to despair. Harberton never spoke. After giving me my instructions, showing me the way around, and dividing up the work, he had lapsed into total silence. His wife and children were used to it, but being in the presence of a man who never spoke was starting to effect me. He would rise at dawn, put some meat or smoked fish, along with bread and onion, in his canvas knapsack, and set off for the mountains, returning only as night fell.

Once, when there was a snowstorm and he did not come back all night, I went out the following morning to look for him, thinking he might have met with accident. I found him on one of the highest peaks, having taken shelter in a natural cave in the rocks, smoking his octoroon pipe and staring out at the surrounding landscape. The Beagle Channel was below us, like a green path blooming with foam – the only touch of color, as everything else was completely white. The last foothills of the Andes, which come to an end in Tierra del Fuego, lay there like broken, moons, and the island of Navarino itself seemed like the beginning of another strange world.

©AnneManleyArtist

Follow Anne Manley on Instagram and on annemanley724.wixsite.com